Industry versus Humanities – ReSoURCE’s Science Communication Presented at an International Conference

It might not be obvious why a refractory recycling research project is presented at an international conference in Belfast that is mainly focusing on a cultural history context. But to compare science communication and outreach in an industrial research project to projects in humanities, it was the perfect place to be.

Before I joined the ReSoURCE team as a professional science communicator, I worked more than 20 years in archaeology – a discipline that is traditionally keen on following an interdisciplinary approach and that was in the projects I was involved in almost always linked to Geology, Physics, and Biology to name only a few. In former projects I had seen that there is sometimes a difference in communication and outreach but also in general management tasks in the different entities. In the project ReSoURCE we have partners from very diverse backgrounds; there is a university, several private research institutes and smaller businesses of different sizes and the large refractory company RHI Magnesita. All of them have their own understanding regarding the need of science communication and they also have very different set-ups when it comes to professional communicators in their entity. To take a closer look at the similarities and differences not just between our partner entities but also in general between humanities and industry, I handed in a paper at the EAA session “Coordination, Dissemination, and Communication” by Helena Seidl da Fonseca at the EAA in Belfast this year that got accepted.

I must say that this was the most interesting topic I have worked on in a while. For example, coming from entities that are most closely connected to universities and their academic research, I was not aware of the large investment businesses like RHI Magnesita make in research and development.

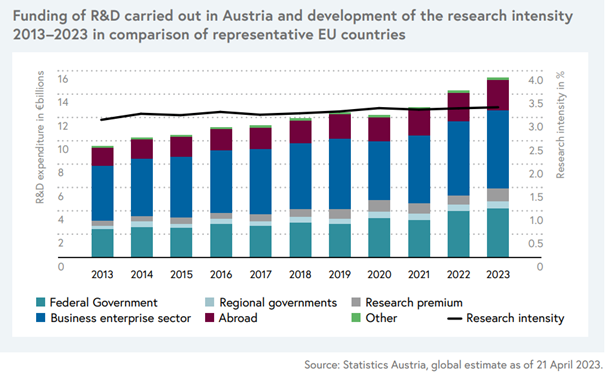

According to Statistics Austria, the business enterprise sector invests – traditionally – more than the federal and regional governments together. Even taking the research premium into account, the businesses are still in the lead. But why do they invest so much money? The main reasons for industrial entities to invest in research are innovation and competitive advantage, product development of course, cost reduction, to gain protected intellectual property, maybe to improve their image and reputation, and surely many more. In humanities, the main reason for an investment is educational value, preservation of cultural heritage, legal and ethical responsibility amongst others. But I realized that one of the reasons here is, too, improving the product and adjusting it to the customer’s needs. This phrase might sound weird, but it is true: the questions we ask in Humanities that are the starting point for our research are usually inspired by the society we live in (our customer), and to which we want to contribute to with our research. The outcome – hopefully – ends up being presented in an exhibition or a documentary or being published in a book (our product).

Much like the reasons for the research itself, the motivation for science communication is similar, too, to a certain degree: reputation of the entity or the participating scientists, leadership in their specific field, and employer branding – all these are true for both. While they also both try to reach and engage the broader public, I assume that this might often be more focused on specific stakeholders when it comes to industrial research. In general, the humanities are much closer to the educational and purely academic sphere than science conducted in the business or industrial sector. Of course, this also influences the nature of science communication in the various areas.

But the main difference that I have seen so far has much less to do with these aspects and more with the resources that are available for scientists. It has a massive impact on the science communication if you can collaborate with a professional communicator and have access to their professional knowledge and tools. A press release for example that needs to be send out is daily business for every university and every bigger company. The communicator will let you know what the best timing is, how such a text needs to be structured, which pictures you can and should use. They will take care of sending it out and it will magically appear on online platforms and in print. This “magic” is quite often done by press service agencies that are well paid for this kind of support. It is a very different game when a small entity, who has no expert on the team with this kind of specific knowledge, must carry out a similar thing.

This is an even bigger problem when we consider that most scientists are not educated in communication. This is unfortunately true no matter the field or specification. All students learn a very special way to communicate when they are trained at the university. It is almost a special language with its own commonly (common only in the specific field) know wordings and sometime even grammar. On top of that, scientists structure their content differently: in the spirit of transparency and with the goal to allow others to gather information first and discuss opinions later, they usually give a lot of background information before they come to the important points. Communicators are well familiar with the pyramidal structuring of communication content, which mentions the core message first and gives more detail only afterwards. Basically, scientists are trained to communicate in exactly the opposite way. One conclusion I made in my presentation is hence the importance to make sure that professional communication is part of the curriculum in all disciplines.

The result of my deeper insight into this topic is that the differences between what looked so different from the outside are actually not that big. The biggest difference is the size of the company, as smaller companies simply don’t have the resources they need to communicate professionally. We must therefore continue to work on training scientists and ensuring that they themselves learn to communicate with the general public.

Author’s Portrait

Carmen Loew

Carmen Loew, Magistra Artium, is the project ReSoURCE’s science communicator. She studied Archaeology at the Universities of Saarbrücken and Bamberg and managed projects in research and rescue archaeology in Germany and France before she focused on science communication in 2015. She is a certified PR manager, Fundraising manager, Marketing & Sales assistant, and cultural educator. Her (research) interests are science communication and outreach, crisis communication as well as intercultural communication.